Thinking About Innovation

Last week I linked to a presentation I gave about innovation to VCU and some people seem to have liked it, so I figured I'd repost it here with a bit more context.

A few months ago I got an email from a BrandCenter student named Adam Wiese about adding a brand to Brand Tags. We got to chatting a bit and he suggested I should come down to BrandCenter and give a talk. I told him I'd be happy to and next think I knew I had an email from Caley Cantrell, who teaches innovation at the school, asking me if I'd like to come down.

I said yes, scheduled it for a few months later and all was well until about a month before when I realized that I was being asked to tackle a topic I sort of hate discussing. The word innovation makes my skin crawl a bit. It's so overused at this point that it's all but meaningless and I had no idea where to begin. So, that's where I began ... I decided that if I was going to go talk about innovation I was going to do my best to really define the word. In the end, I'm not sure I totally succeeded, but I did uncover a whole bunch of very interesting writing on the topic. Especially interesting to me were some of the ideas of early 20th century Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, who wrote extensively on entrepreneurialism and what he saw as an outgrowth: Innovation.

Okay, now a pause for the presentation.

Like I said, I'm not sure I succeeded at defining it, but I found Schumpeter's framework of invention, innovation and diffusion really helped guide my thinking. Schumpeter actually simplifies the ideas even further when he talks about entrepreneurs. Essentially he wrote that there were three separate roles in the innovation process: The capitalist, who provides the money, the inventor, who creates the idea and the entrepreneur, who adapts the idea and brings it to market. While these roles are often played by a single person, it does not make them a separate role. (He goes on to talk about the value of separating the financial burden from the entrepreneur to enable them to focus on the task at hand.)

I think this separation is often overlooked, and so did Schumpter:

Economic leadership in particular must hence be distinguished from "invention." As long as they are not carried into practice, inventions are economically irrelevant. And to carry any improvement into effect is a task entirely different from the inventing of it, and a task, moreover, requiring entirely different kinds of aptitudes. Although entrepreneurs of course may be inventors just as they may be capitalists, they are inventors not by nature of their function but by coincidence and vice versa. Besides, the innovations which it is the function of entrepreneurs to carry out need not necessarily be any inventions at all. It is, therefore, not advisable, and it may be downright misleading, to stress the element of invention as much as many writers do.

Finally, a bit about the role of research and its impact on innovation. In 1980 Robert Hayes and William Abernathy wrote a now well-known Harvard Business Review article titled Managing Our Way to Economic Decline. In it they wrote this about the role of research in organizations:

Our experience suggests that, to an unprecedented degree, success in most industries today requires an organizational commitment to compete in the marketplace on technological grounds--that is, to compete over the long run by offering superior products. Yet, guided by what they took to be the newest and best principles of management, American managers have increasingly directed their attention elsewhere. These new principles, despite their sophistication and widespread usefulness, encourage a preference for (1) analytic detachment rather than the insight that comes from hands-on experience and (2) short-term cost reduction rather than long-term development of technological competitiveness. It is this new managerial gospel, we feel, that has played a major role in undermining the vigor of American industry.

Twenty two years later, Clayton Christensen wrote this in a Technology Review article titled Rules of Innovation:

What drove Sony's shift from a disruptive to a sustaining innovation strategy? Prior to 1980, all new product launch decisions were made by cofounder Akio Morita and a trusted team of associates. They never did market research, believing that if markets did not exist they could not be analyzed. Their process for assessing new opportunities relied on personal intuition. In the 1980s Morita withdrew from active management in order to be more involved in Japanese politics. The company consequently began hiring marketing and product-planning professionals who brought with them data-intensive, analytical processes of doing market research. Those processes were very good at uncovering unmet customer needs in existing product markets. But making the intuitive bets required to launch disruptive businesses became impossible.

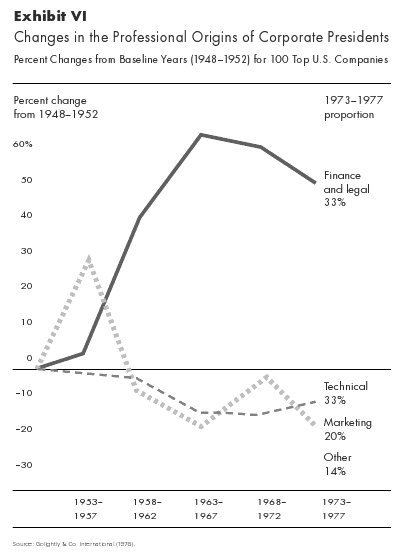

To be honest, I don't feel like we've gotten anywhere on this one. Christensen made the same point as Hayes/Abernathy 22 years later and here we are, eight years after that, complaining about the same thing (or praising Steve Jobs for not subscribing). Interestingly, Managing Our Way to Economic Decline places much of the blame on the shift in corporate mindset from a one that makes someone with a technical background president, to one that makes someone with a financial/legal background president (see chart below).

I hadn't ever seen this, and would be quite curious to see what this chart would look like with the last thirty years on it (I imagine finance and legal has taken an even larger chunk). I don't really have some great insight here, but it does go a long way to explaining why so many large organizations are so disappointing from an innovation perspective.

Anyway, I could keep going and going and going, but I'm going to stop (somewhat abruptly) here. I have some more quotes and stuff I collected and I quote post if folks are so inclined, but I can't imagine you've actually made it to the bottom of all this, so maybe that's best done in another post.