The Fermi Paradox

In the Fermi episode of Rationally Speaking Julia Galef makes a really interesting point I hadn't read/considered before:

In the Fermi episode of Rationally Speaking Julia Galef makes a really interesting point I hadn't read/considered before:

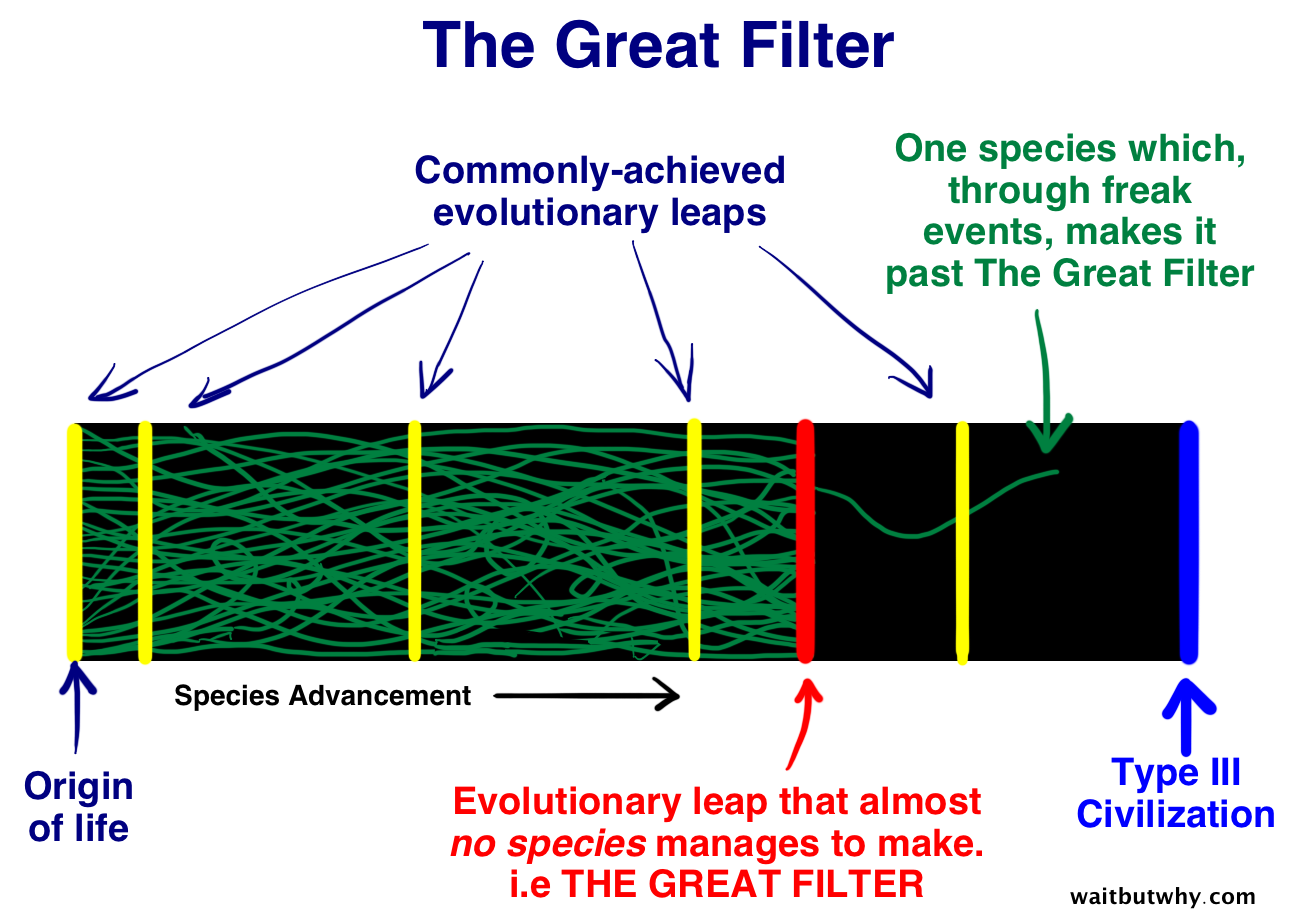

Doesn't it seem like human-level intelligence probably isn't mindbogglingly rare if we got several part-way successes just on Earth? Wouldn't it be a weird world in which it was pretty easy to — pretty easy in the sense that evolution did it multiple times on Earth — to create “part-way to human level”intelligence, but there was only one actual human-level intelligence in the whole universe?Stephen Webb, who she's interviewing, responds with this:

Well, I'm not arguing necessarily that the barrier is there, but if you look at Earth, of the 50 billion species or however many there have been, there's only one species that is remotely capable of delivering a starfaring civilization, and that would be us. I think that's because we have a very, very specific set of attributes that happened to enable us to do this.

It actually kind of reminds me of one of my favorite books of the last few years, The Most Human Human. The book tackles the AI question in reverse. Rather than trying to understand how to make computers more like humans it wonders how to differentiate what we do as humans from what computers can already do. (The context for the whole book is that the author, Brian Christian, is getting ready to compete as a human in the Loebner Prize, the famous competition where computers compete to see who can pass the Turing Test and fool a human into thinking they're another human.) By flipping the perspective on the question you get very different kinds of answers.

Finally, since we're talking about the Fermi Paradox, The Atlantic had a good piece about "Why Earth's History Appears So Miraculous" which although it doesn't mention Fermi, basically tackles the same questions. For instance, is it a good sign or a bad sign that we haven't already destroyed ourselves?So now you can imagine a world where the probability per year of nuclear war is actually 50 percent. So then the first year, the first half of worlds get nuked. Then the next year half of those survivor worlds get nuked. And so on. So in this very scary scenario—still after 70 years—if you have a big enough universe or many parallel universes, you’re still going to have some observers [left over] who say ‘Hey! It looks like we’re pretty safe!’ And again they will get a very nasty surprise when the nukes start flying.