Parable of Two Watchmakers [Framework of the Day]

Exploring Herbert Simon's Parable of Two Watchmakers and its application to complex systems and business

Another framework of the day. If you haven't read the others, the links are all at the bottom. I'm working on a book of mental models and sharing some of the research and writing as I go. This post actually started in writing about Conway's Law, which is coming soon. I felt like I had to get this out first, as I would need to rely on some of the research in giving the Law its due. Thanks for reading and please let me know what you think, pass this link on, and subscribe to the email if you haven't done it already. Thanks for reading.

This framework is a little different than the ones before as it doesn't come with a nice diagram or four box. Rather, the Parable of Two Watchmakers is just that: A story about two people putting together complicated mechanical objects. The parable comes from a paper called "The Architecture of Complexity" written by Nobel-prize winning economist Herbert Simon (you might remember Simon from the theory of satisficing). Beyond being a brilliant economist, Simon was also a major thinker in the worlds of political science, psychology, systems, complexity, and artificial intelligence (in doing this research he climbed up the ranks of my intellectual heroes).

In his 1962 he laid out an argument for how complexity emerges, which is largely focused on the central role of hierarchy in complex systems. To start, let's define hierarchy so we're all on the same page. Here's Simon:

This framework is a little different than the ones before as it doesn't come with a nice diagram or four box. Rather, the Parable of Two Watchmakers is just that: A story about two people putting together complicated mechanical objects. The parable comes from a paper called "The Architecture of Complexity" written by Nobel-prize winning economist Herbert Simon (you might remember Simon from the theory of satisficing). Beyond being a brilliant economist, Simon was also a major thinker in the worlds of political science, psychology, systems, complexity, and artificial intelligence (in doing this research he climbed up the ranks of my intellectual heroes).

In his 1962 he laid out an argument for how complexity emerges, which is largely focused on the central role of hierarchy in complex systems. To start, let's define hierarchy so we're all on the same page. Here's Simon:

This framework is a little different than the ones before as it doesn't come with a nice diagram or four box. Rather, the Parable of Two Watchmakers is just that: A story about two people putting together complicated mechanical objects. The parable comes from a paper called "The Architecture of Complexity" written by Nobel-prize winning economist Herbert Simon (you might remember Simon from the theory of satisficing). Beyond being a brilliant economist, Simon was also a major thinker in the worlds of political science, psychology, systems, complexity, and artificial intelligence (in doing this research he climbed up the ranks of my intellectual heroes).

In his 1962 he laid out an argument for how complexity emerges, which is largely focused on the central role of hierarchy in complex systems. To start, let's define hierarchy so we're all on the same page. Here's Simon:

This framework is a little different than the ones before as it doesn't come with a nice diagram or four box. Rather, the Parable of Two Watchmakers is just that: A story about two people putting together complicated mechanical objects. The parable comes from a paper called "The Architecture of Complexity" written by Nobel-prize winning economist Herbert Simon (you might remember Simon from the theory of satisficing). Beyond being a brilliant economist, Simon was also a major thinker in the worlds of political science, psychology, systems, complexity, and artificial intelligence (in doing this research he climbed up the ranks of my intellectual heroes).

In his 1962 he laid out an argument for how complexity emerges, which is largely focused on the central role of hierarchy in complex systems. To start, let's define hierarchy so we're all on the same page. Here's Simon:

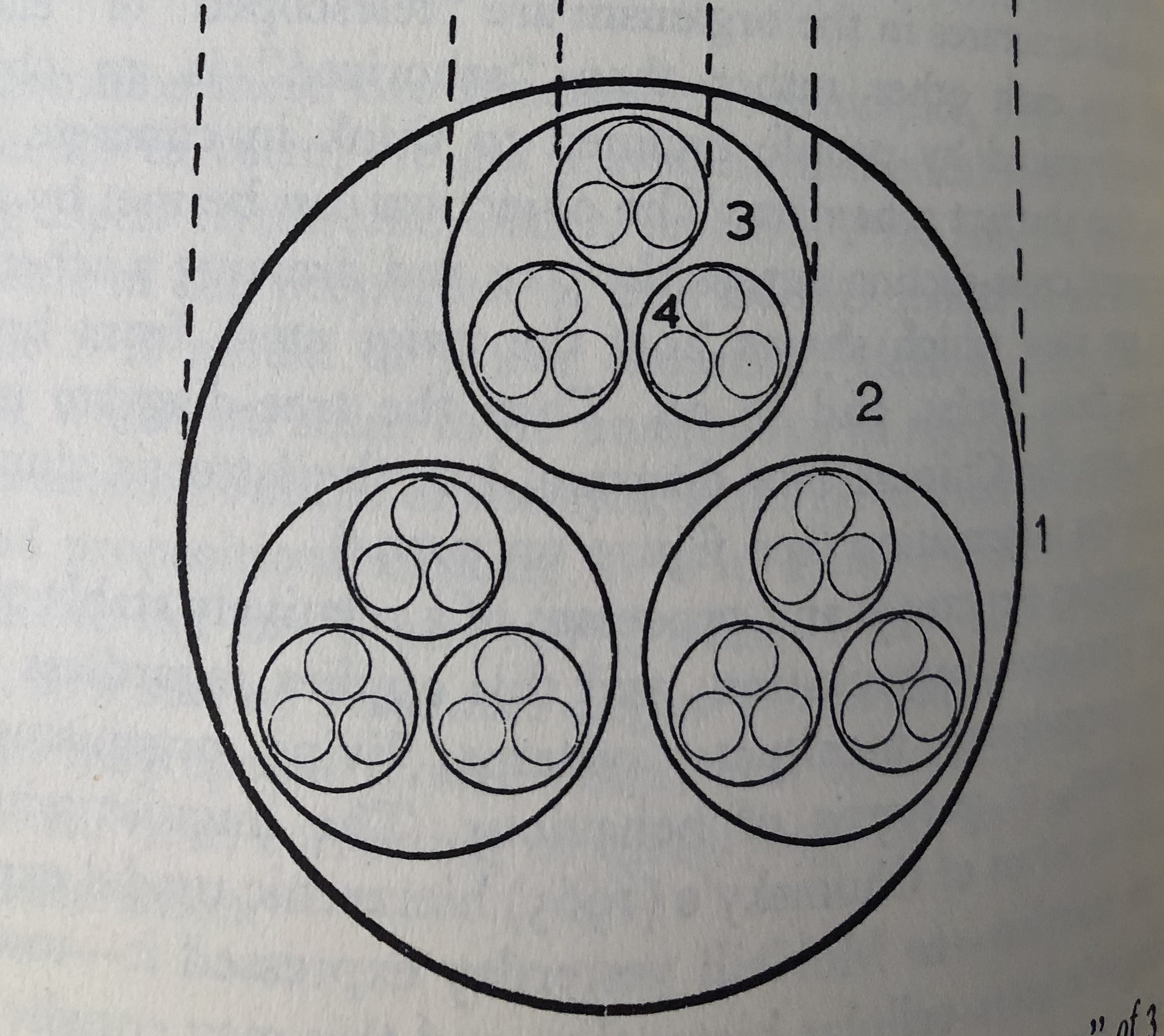

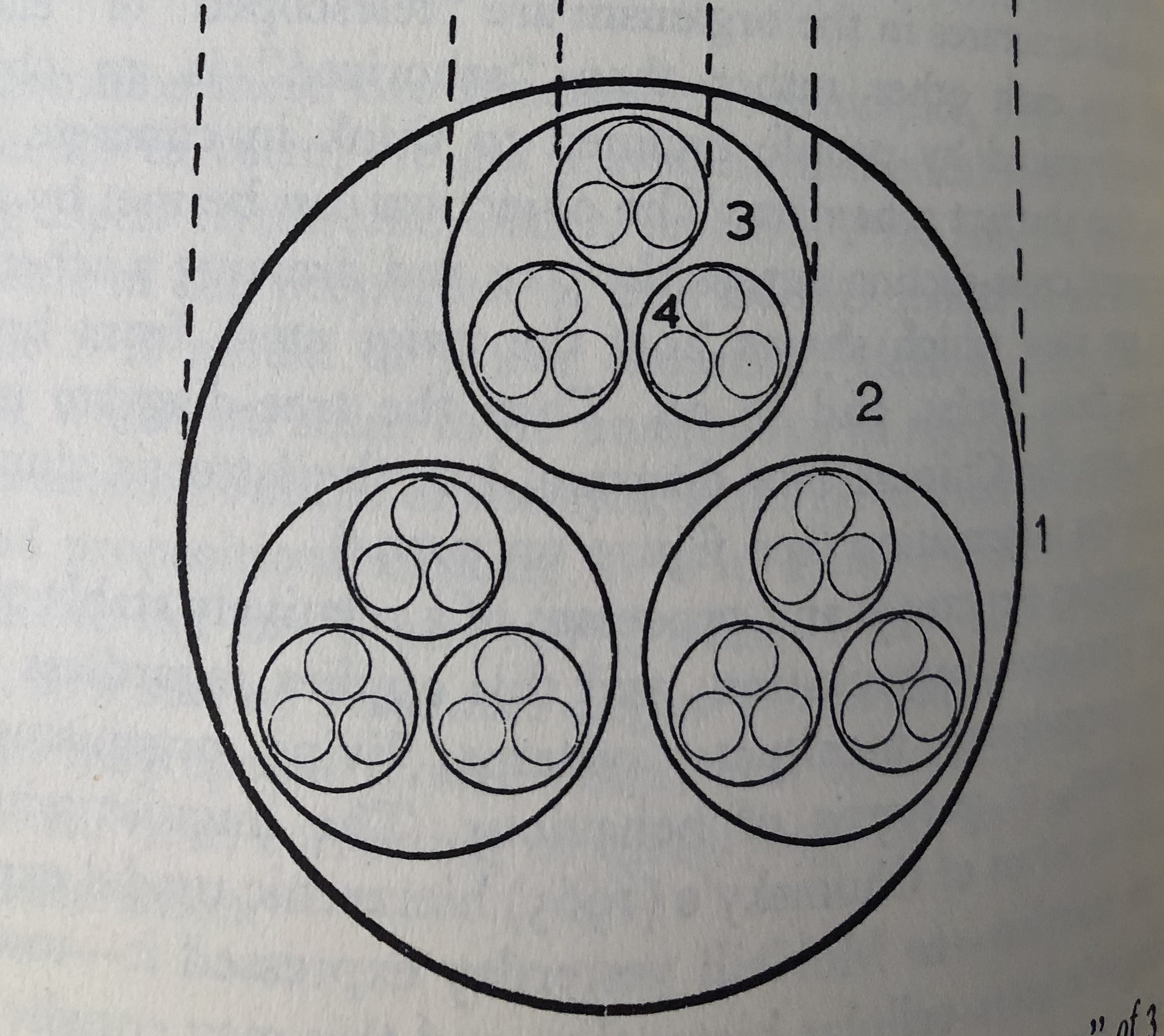

Etymologically, the word “hierarchy” has had a narrower meaning than I am giving it here. The term has generally been used to refer to a complex system in which each of the subsystems is subordinated by an authority relation to the system it belongs to. More exactly, in a hierarchic formal organization, each system consists of a “boss” and a set of subordinate subsystems. Each of the subsystems has a “boss” who is the immediate subordinate of the boss of the system. We shall want to consider systems in which the relations among subsystems are more complex than in the formal organizational hierarchy just described. We shall want to include systems in which there is no relation of subordination among subsystems. (In fact, even in human organizations, the formal hierarchy exists only on paper; the real flesh-and-blood organization has many inter-part relations other than the lines of formal authority.) For lack of a better term, I shall use hierarchy in the broader sense introduced in the previous paragraphs, to refer to all complex systems analyzable into successive sets of subsystems, and speak of “formal hierarchy” when I want to refer to the more specialized concept.So it's more or less the way we think of it, except he is drawing a distinction to the formal hierarchy we see in an org chart where each subordinate has just one boss and the informal hierarchy that actually exists inside organizations, where subordinates interact in a variety of ways. And he points out the many complex systems we find hierarchy, including biological systems, "The hierarchical structure of biological systems is a familiar fact. Taking the cell as the building block, we find cells organized into tissues, tissues into organs, organs into systems. Moving downward from the cell, well-defined subsystems — for example, nucleus, cell membrane, microsomes, mitochondria, and so on — have been identified in animal cells." The question is why did all these systems come to be arranged this way and what can we learn from them? Here Simon turns to story:

Let me introduce the topic of evolution with a parable. There once were two watchmakers, named Hora and Tempus, who manufactured very fine watches. Both of them were highly regarded, and the phones in their workshops rang frequently — new customers were constantly calling them. However, Hora prospered, while Tempus became poorer and poorer and finally lost his shop. What was the reason? The watches the men made consisted of about 1,000 parts each. Tempus had so constructed his that if he had one partly assembled and had to put it down — to answer the phone say— it immediately fell to pieces and had to be reassembled from the elements. The better the customers liked his watches, the more they phoned him, the more difficult it became for him to find enough uninterrupted time to finish a watch. The watches that Hora made were no less complex than those of Tempus. But he had designed them so that he could put together subassemblies of about ten elements each. Ten of these subassemblies, again, could be put together into a larger subassembly; and a system of ten of the latter subassemblies constituted the whole watch. Hence, when Hora had to put down a partly assembled watch in order to answer the phone, he lost only a small part of his work, and he assembled his watches in only a fraction of the man-hours it took Tempus.Whether the complexity emerges from the hierarchy or the hierarchy from the complexity, he illustrates clearly why we see this pattern all around us and articulates the value of the approach. It's not just hierarchy, he goes on to explain, but also modularity (which he refers to as near-decomposability) that appears to be a fundamental property of complex systems. That is, each of the subsystems operates both independently and as part of the whole. As Simon puts it, "Intra-component linkages are generally stronger than intercomponent linkages" or, even more simply, "In a formal organization there will generally be more interaction, on the average, between two employees who are members of the same department than between two employees from different departments." Why is that? Well, for one, it's an efficiency thing. Just as we see inside organizations, we want to use specialized resources in a specialized way. But beyond that, as Simon outlines in the parable, it's also about resiliency: By relying on subsystems you have a defense against catastrophic failure when one piece of the whole breaks down. Just as Hora was able to quickly start building again when he put something down, any system made up of subsystems should be much more capable of dealing with changes in environment. It works in organisms, companies, and even empires, as Simon pointed out in The Sciences of the Artificial:

We have not exhausted the categories of complex systems to which the watchmaker argument can reasonably be applied. Philip assembled his Macedonian empire and gave it to his son, to be later combined with the Persian subassembly and others into Alexander's greater system. On Alexander's death his empire did not crumble to dust but fragmented into some of the major subsystems that had composed it.

Hopefully the application of this framework is pretty clear (and also instructive) in every day business life. Interestingly, Simon's theories were the ultimate inspiration for a management fad we saw burn bright (and flame out) just a few years ago: Holacracy, the fluid organizational structure made up of self-organizing teams. Invented by Brian Robertson and made famous by Tony Hsieh and Zappos, the method (it's a registered trademark) is based on ideas about "holons" from Hungarian author and journalist Arthur Koestler. In his 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine, Koestler repeats Simon's story of Tempus and Hora and then goes on to theorize that holons (a name he coined "from the Greek holos—whole, with the suffix on (cf. neutron, proton) suggesting a particle or part") are "meant to supply the missing link between atomism and holism, and to supplant the dualistic way of thinking in terms of 'parts' and 'wholes,' which is so deeply engrained in our mental habits, by a multi-levelled, stratified approach. A hierarchically-organized whole cannot be "reduced" to its elementary parts; but it can be 'dissected' into its constituent branches of holons, represented by the nodes of the tree-diagram, while the lines connecting the holons stand for channels of communication, control or transportation, as the case may be."

Holacracy aside, there's a ton of goodness in the parable and the architecture of modularity that it posits as critical. It's not an accident that every company is built this way and as we think about those companies designing systems, it's also not surprising many of those should also follow suit (a good lead-in for Conway's Law, which is up next). Although I'm pretty out of words at this point, Simon also applies the same hierarchy/modularity concept to problem solving and there's a pretty good argument to be made that the "latticework of models" Charlier Munger described in his 1994 USC Business School Commencement Address would fit the framework.

Bibliography:

- Egidi, Massimo, and Luigi Marengo. "Cognition, institutions, near decomposability: rethinking Herbert Simon's contribution." (2002).

- Egidi, Massimo. "Organizational learning, problem solving and the division of labour." Economics, bounded rationality and the cognitive revolution. Aldershot: Edward Elgar (1992): 148-73.

- Koestler, Arthur, and John R. Smythies. Beyond Reductionism, New Perspectives in the Life Sciences [Proceedings of] the Alpbach Symposium [1968]. (1972).

- Koestler, Arthur. "The ghost in the machine." (1967).

- Radner, Roy. "Hierarchy: The economics of managing." Journal of economic literature 30.3 (1992): 1382-1415.

- Simon, Herbert A. "Near decomposability and the speed of evolution." Industrial and corporate change 11.3 (2002): 587-599.

- Simon, Herbert A. "The Architecture of Complexity." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 106.6 (1962): 467-482.

- Simon, Herbert A. "The science of design: Creating the artificial." Design Issues (1988): 67-82.

- Simon, Herbert A. The sciences of the artificial. MIT press, 1996.

- Conway's Law

- Known Unknowns

- Pace Layers

- Parable of Two Watchmakers

- Pareto Principle (aka 80/20 Rule)

- Variance Spectrum