Variance Spectrum [Framework of the Day]

The Variance Spectrum framework is explained, illustrating the variance of marketing's output and its implications for organizational decision-making.

If you haven't read any of these yet, the gist is that I'm writing a book about mental models and writing these notes up as I go. You can find links at the bottom to the other frameworks I've written. If you haven't already, please subscribe to the email and share these posts with anyone you think might enjoy them. I really appreciate it.

The vast majority of the models I've written about were ones that I discovered at one time or another and have adopted for my own knowledge portfolio. The Variance Spectrum, on the other hand, I came up with. Its origin was in trying to answer a question about why there wasn't a centralized "system of record" for marketing in the same way you would find one in finance (ERP) or sales (CRM). My best answer was that the output of marketing made it particularly difficult to design a system that could satisfy the needs of all its users. Specifically, I felt as though the variance of marketing's output, the fact that each campaign and piece of content is meant to be different than the one that came before it, made for an environment that at first seemed opposed to the basics of systemization that the rest of a company had come to accept.

To illustrate the idea I plotted a spectrum. The left side represented zero variance, the realm of manufacturing and Six Sigma, and the right was 100 percent variance, where R&D and innovation reign supreme.

While the poles of the spectrum help explain it, it's what you place in the middle that makes it powerful. For example, we could plot the rest of the departments in a company by the average variance of their output (finance is particularly low since so much of the department's output is "governed" -- quite literally the government sets GAAP accounting standards and mandates specific tax forms). Sales is somewhere in the middle: A pretty good mix of process and methodology plus the "art of the deal". Marketing, meanwhile, sits off to the right, just behind R&D.

While the poles of the spectrum help explain it, it's what you place in the middle that makes it powerful. For example, we could plot the rest of the departments in a company by the average variance of their output (finance is particularly low since so much of the department's output is "governed" -- quite literally the government sets GAAP accounting standards and mandates specific tax forms). Sales is somewhere in the middle: A pretty good mix of process and methodology plus the "art of the deal". Marketing, meanwhile, sits off to the right, just behind R&D.

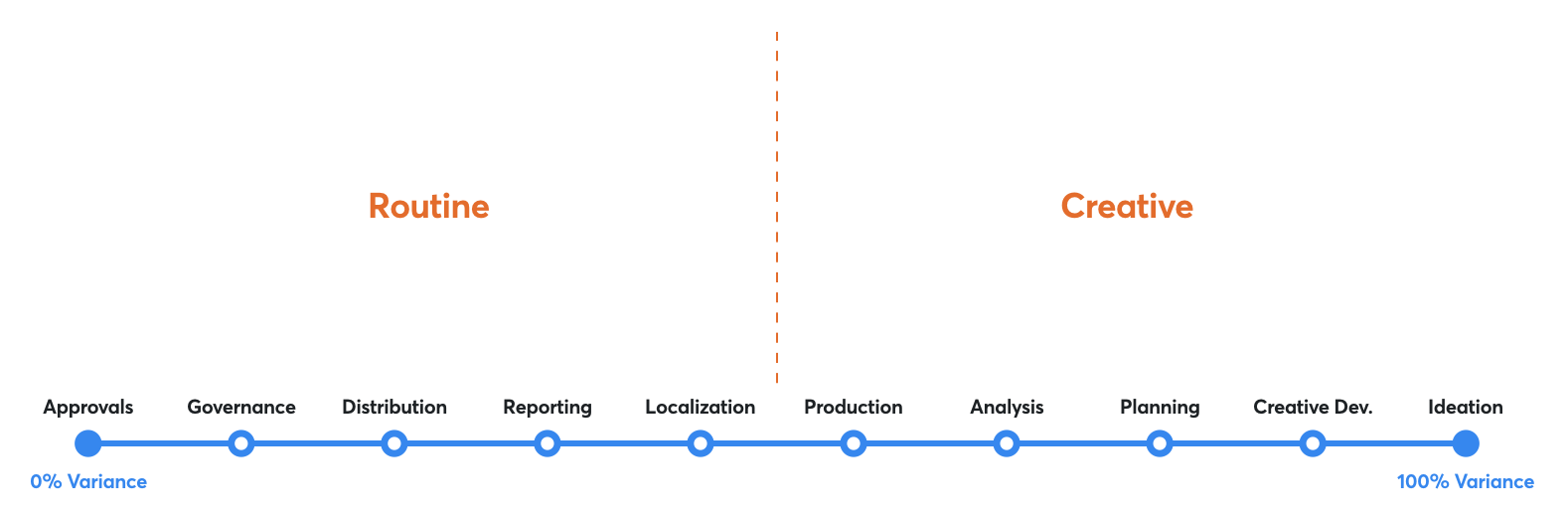

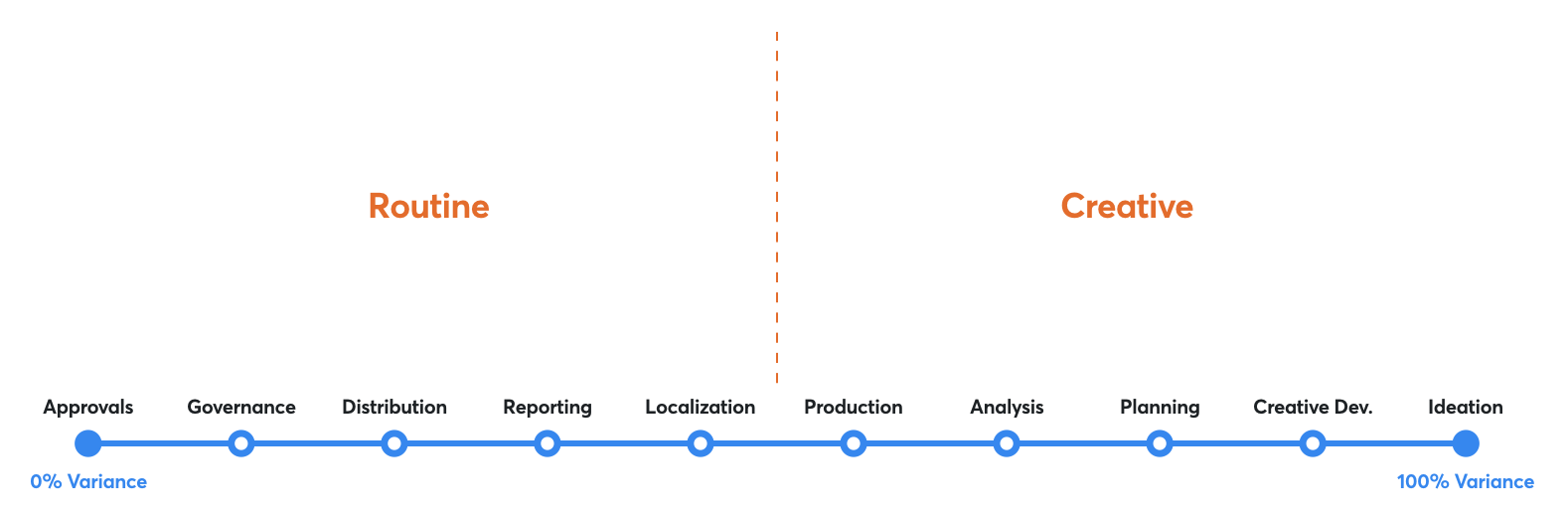

But that's just the first layer. Like so many parts of an organization (and as described in my essays on both The Parable of Two Watchmakers and Conway's Law), companies are hierarchical and at any point in the spectrum you can drill in and find a whole new spectrum of activities that range from low variance to high variance. That is, while finance may be "low variance" on average thanks to government standards, forecasting and modeling is most certainly a high variance function: Something that must be imagined in original ways depending on a number of variables include the company, and its products and markets (to name a few). Zooming in on marketing we find a whole new set of processes that can themselves be plotted based on the variance of their output, with governance far to the low variance side and creative development clearly on the other pole. Another way to articulate these differences is that the low variance side represents the routine processes and the right the creative.

But that's just the first layer. Like so many parts of an organization (and as described in my essays on both The Parable of Two Watchmakers and Conway's Law), companies are hierarchical and at any point in the spectrum you can drill in and find a whole new spectrum of activities that range from low variance to high variance. That is, while finance may be "low variance" on average thanks to government standards, forecasting and modeling is most certainly a high variance function: Something that must be imagined in original ways depending on a number of variables include the company, and its products and markets (to name a few). Zooming in on marketing we find a whole new set of processes that can themselves be plotted based on the variance of their output, with governance far to the low variance side and creative development clearly on the other pole. Another way to articulate these differences is that the low variance side represents the routine processes and the right the creative.

While I haven't seen anyone else plot things quite this way, this idea, that there are fundamentally different kinds of tasks within a company, is not new. Organizational theorists Richard Cyert, Herbert Simon, and Donald Trow, also noted this duality in paper from 1956 called "Observation of a Business Decision":1

While I haven't seen anyone else plot things quite this way, this idea, that there are fundamentally different kinds of tasks within a company, is not new. Organizational theorists Richard Cyert, Herbert Simon, and Donald Trow, also noted this duality in paper from 1956 called "Observation of a Business Decision":1

While this is primarily a framework for thinking about process, there's a more personal way to think about the variance spectrum as it relates to giving feedback to others. It's a common occurrence that employees over-or-misinterpret the feedback of more senior members of the team. I experienced this many times myself in my role as CEO. Because words are often taken literally from the leader of a company, an aside about something like color choice in a design comp can be easily misconstrued as an order to change when it wasn't meant that way. The variance spectrum in that context can be used to make explicit where the feedback falls: Is it a low variance order you expect to be acted on or a high variance comment that is simply your two cents? I found this could help avoid ambiguity and also make it more clear I respected their expertise.

Footnotes:

While this is primarily a framework for thinking about process, there's a more personal way to think about the variance spectrum as it relates to giving feedback to others. It's a common occurrence that employees over-or-misinterpret the feedback of more senior members of the team. I experienced this many times myself in my role as CEO. Because words are often taken literally from the leader of a company, an aside about something like color choice in a design comp can be easily misconstrued as an order to change when it wasn't meant that way. The variance spectrum in that context can be used to make explicit where the feedback falls: Is it a low variance order you expect to be acted on or a high variance comment that is simply your two cents? I found this could help avoid ambiguity and also make it more clear I respected their expertise.

Footnotes:

While the poles of the spectrum help explain it, it's what you place in the middle that makes it powerful. For example, we could plot the rest of the departments in a company by the average variance of their output (finance is particularly low since so much of the department's output is "governed" -- quite literally the government sets GAAP accounting standards and mandates specific tax forms). Sales is somewhere in the middle: A pretty good mix of process and methodology plus the "art of the deal". Marketing, meanwhile, sits off to the right, just behind R&D.

While the poles of the spectrum help explain it, it's what you place in the middle that makes it powerful. For example, we could plot the rest of the departments in a company by the average variance of their output (finance is particularly low since so much of the department's output is "governed" -- quite literally the government sets GAAP accounting standards and mandates specific tax forms). Sales is somewhere in the middle: A pretty good mix of process and methodology plus the "art of the deal". Marketing, meanwhile, sits off to the right, just behind R&D.

But that's just the first layer. Like so many parts of an organization (and as described in my essays on both The Parable of Two Watchmakers and Conway's Law), companies are hierarchical and at any point in the spectrum you can drill in and find a whole new spectrum of activities that range from low variance to high variance. That is, while finance may be "low variance" on average thanks to government standards, forecasting and modeling is most certainly a high variance function: Something that must be imagined in original ways depending on a number of variables include the company, and its products and markets (to name a few). Zooming in on marketing we find a whole new set of processes that can themselves be plotted based on the variance of their output, with governance far to the low variance side and creative development clearly on the other pole. Another way to articulate these differences is that the low variance side represents the routine processes and the right the creative.

But that's just the first layer. Like so many parts of an organization (and as described in my essays on both The Parable of Two Watchmakers and Conway's Law), companies are hierarchical and at any point in the spectrum you can drill in and find a whole new spectrum of activities that range from low variance to high variance. That is, while finance may be "low variance" on average thanks to government standards, forecasting and modeling is most certainly a high variance function: Something that must be imagined in original ways depending on a number of variables include the company, and its products and markets (to name a few). Zooming in on marketing we find a whole new set of processes that can themselves be plotted based on the variance of their output, with governance far to the low variance side and creative development clearly on the other pole. Another way to articulate these differences is that the low variance side represents the routine processes and the right the creative.

While I haven't seen anyone else plot things quite this way, this idea, that there are fundamentally different kinds of tasks within a company, is not new. Organizational theorists Richard Cyert, Herbert Simon, and Donald Trow, also noted this duality in paper from 1956 called "Observation of a Business Decision":1

While I haven't seen anyone else plot things quite this way, this idea, that there are fundamentally different kinds of tasks within a company, is not new. Organizational theorists Richard Cyert, Herbert Simon, and Donald Trow, also noted this duality in paper from 1956 called "Observation of a Business Decision":1

At one extreme we have repetitive, well-defined problems (e.g., quality control or production lot-size problems) involving tangible considerations, to which the economic models that call for finding the best among a set of pre-established alternatives can be applied rather literally. In contrast to these highly programmed and usually rather detailed decisions are problems of a non-repetitive sort, often involving basic long-range questions about the whole strategy of the firm or some part of it, arising initially in a highly unstructured form and requiring a great deal of the kinds of search processes listed above. In this whole continuum, from great specificity and repetition to extreme vagueness and uniqueness, we will call decisions that lie toward the former extreme programmed, and those lying toward the latter end non-programmed. This simple dichotomy is just a shorthand for the range of possibilities we have indicated.This also introduces an interesting additional way to think about the spectrum: The left side is representative of those ideas where you have the most clarity about the final goal (in manufacturing you know exactly what you want the output to look like when it's done) and the right the most ambiguity (the goal of R&D is to make something new). For that reason, high variance tasks should also fail far more often than their low variance counterparts: Nine out of ten new product ideas might be a good batting average, but if you are throwing away 90 percent of your manufactured output you've massively failed. Even though it may be tempting, that's not a reason to focus purely on the well-structured, low-variance problems, as Richard Cyert laid out in a 1994 paper titled "Positioning the Organization":

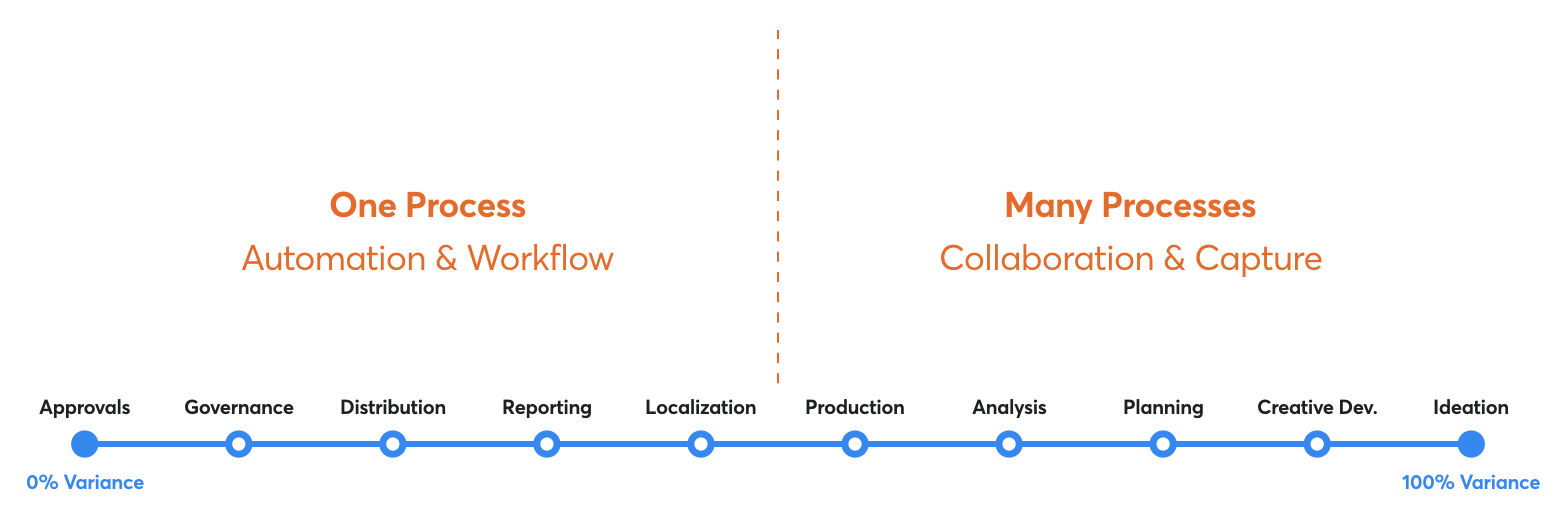

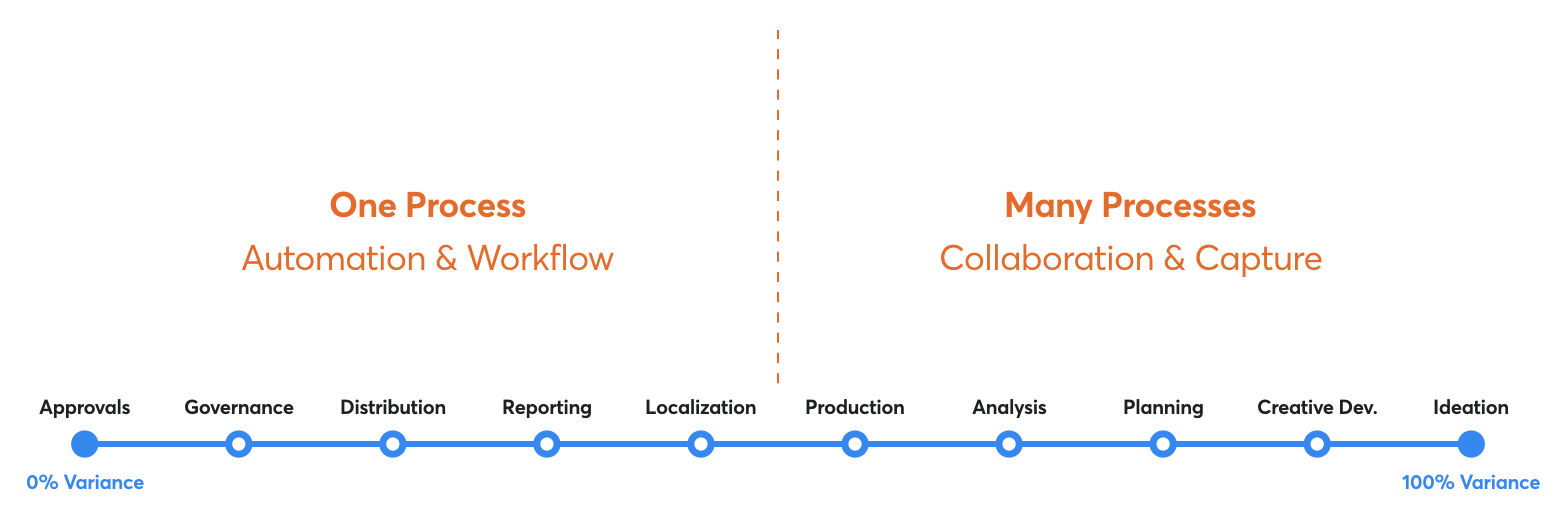

It is difficult to deal with the uncertainty of the future, as one must to relate an organization to others in the industry and to events in the economy that may affect it. One must look ahead to determine what forces are at work and to examine the ways in which they will affect the organization. These activities are less structured and more ambiguous than dealing with concrete problems and, therefore, the CEO may have trouble focusing on them. Many experiments show that structured activity drives out unstructured. For example, it is much easier to answer one's mail than to develop a plan to change the culture of the organization. The implications of change are uncertain and the planning is unstructured. One tends to avoid uncertainty and to concentrate on structured problems for which one can correctly predict the solutions and implications.2Going a level deeper, another way to cut the left and right sides of the spectrum is based on the most appropriate way to solve the problem. For the routine tasks you want to have a single way of doing things in an attempt to push down the variance of the output while on the high variance side you have much more freedom to try different approaches. In software terms this can be expressed as automation and collaboration respectively.

While this is primarily a framework for thinking about process, there's a more personal way to think about the variance spectrum as it relates to giving feedback to others. It's a common occurrence that employees over-or-misinterpret the feedback of more senior members of the team. I experienced this many times myself in my role as CEO. Because words are often taken literally from the leader of a company, an aside about something like color choice in a design comp can be easily misconstrued as an order to change when it wasn't meant that way. The variance spectrum in that context can be used to make explicit where the feedback falls: Is it a low variance order you expect to be acted on or a high variance comment that is simply your two cents? I found this could help avoid ambiguity and also make it more clear I respected their expertise.

Footnotes:

While this is primarily a framework for thinking about process, there's a more personal way to think about the variance spectrum as it relates to giving feedback to others. It's a common occurrence that employees over-or-misinterpret the feedback of more senior members of the team. I experienced this many times myself in my role as CEO. Because words are often taken literally from the leader of a company, an aside about something like color choice in a design comp can be easily misconstrued as an order to change when it wasn't meant that way. The variance spectrum in that context can be used to make explicit where the feedback falls: Is it a low variance order you expect to be acted on or a high variance comment that is simply your two cents? I found this could help avoid ambiguity and also make it more clear I respected their expertise.

Footnotes:

- This paper is kind of amazing to read. It feels revolutionary to actually look at how specific decisions come to be made within a company.↑

- There's a whole other really interesting area to explore here that I'm mostly skipping over about using the variance spectrum to help decide types of problems and the mix of work. Although I don't have a specific model (hence why this is a footnote), the idea that you should decide on your portfolio of activities based on having a good diversity of work across the spectrum is fascinating and seems like a good idea. It's also in line with a point Herbert Simon makes at the very beginning of his book Administrative Behavior: "Although any practical activity involves both 'deciding' and 'doing,' it has not commonly been recognized that a theory of administration should be concerned with the processes of decision as well as with the processes of action. This neglect perhaps stems from the notion that decision-making is confined to the formulation of over-all policy. On the contrary, the process of decision does not come to an end when the general purpose of an organization has been determined. The task of 'deciding' pervades the entire administrative organization quite as much as does the task of 'doing'- indeed, it is integrally tied up with the latter. A general theory of administration must include principles of organization that will insure correct decision-making, just as it must include principles that will insure effective action."↑

- Cyert, R. M., Simon, H. A., & Trow, D. B. (1956). Observation of a business decision. The Journal of Business, 29(4), 237-248.

- Cyert, R. M. (1994). Positioning the organization. Interfaces, 24(2), 101-104.

- Dong, J., March, J. G., & Workiewicz, M. (2017). On organizing: an interview with James G. March. Journal of Organization Design, 6(1), 14.

- March, J. G. (2010). The ambiguities of experience. Cornell University Press.

- Simon, H. A. (2013). Administrative behavior. Simon and Schuster.

- Stene, E. O. (1940). An approach to a science of administration. American Political Science Review, 34(6), 1124-1137.